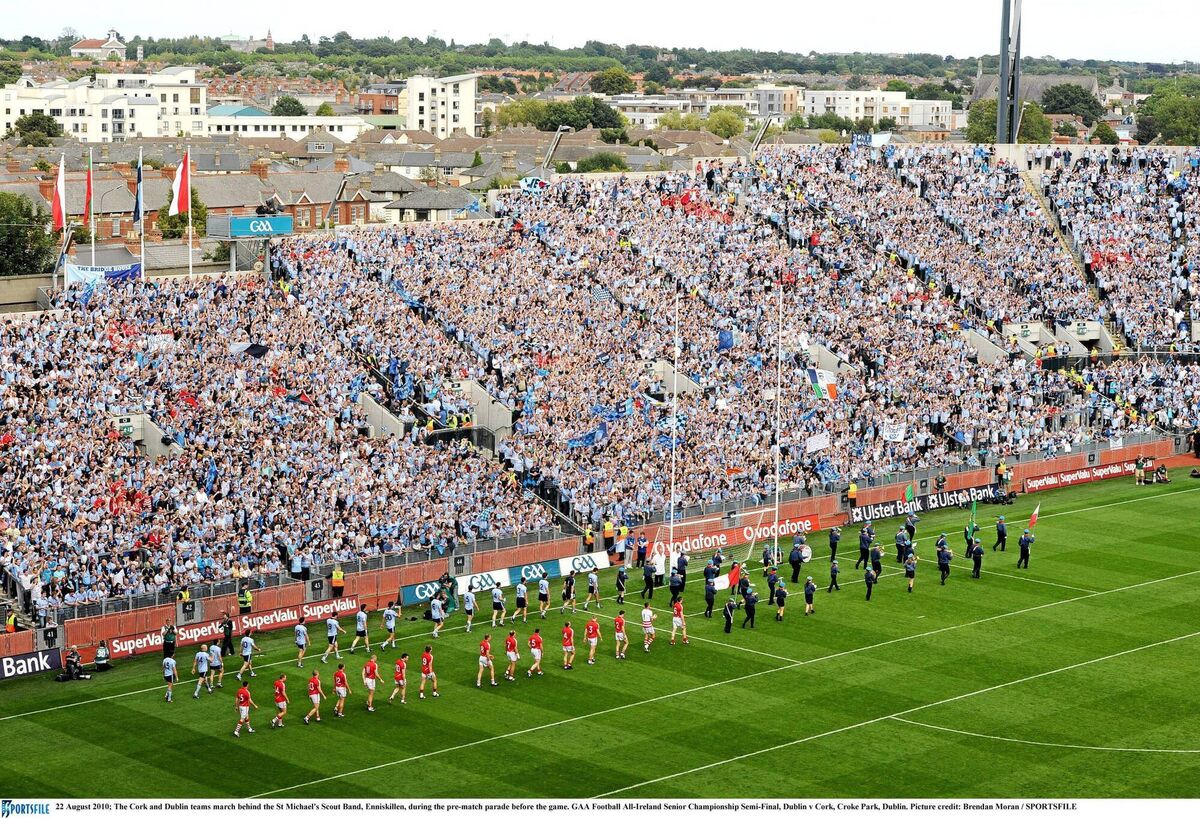

The day Cork stunned Dublin: The loudest All-Ireland semi-final ever at Croke Park

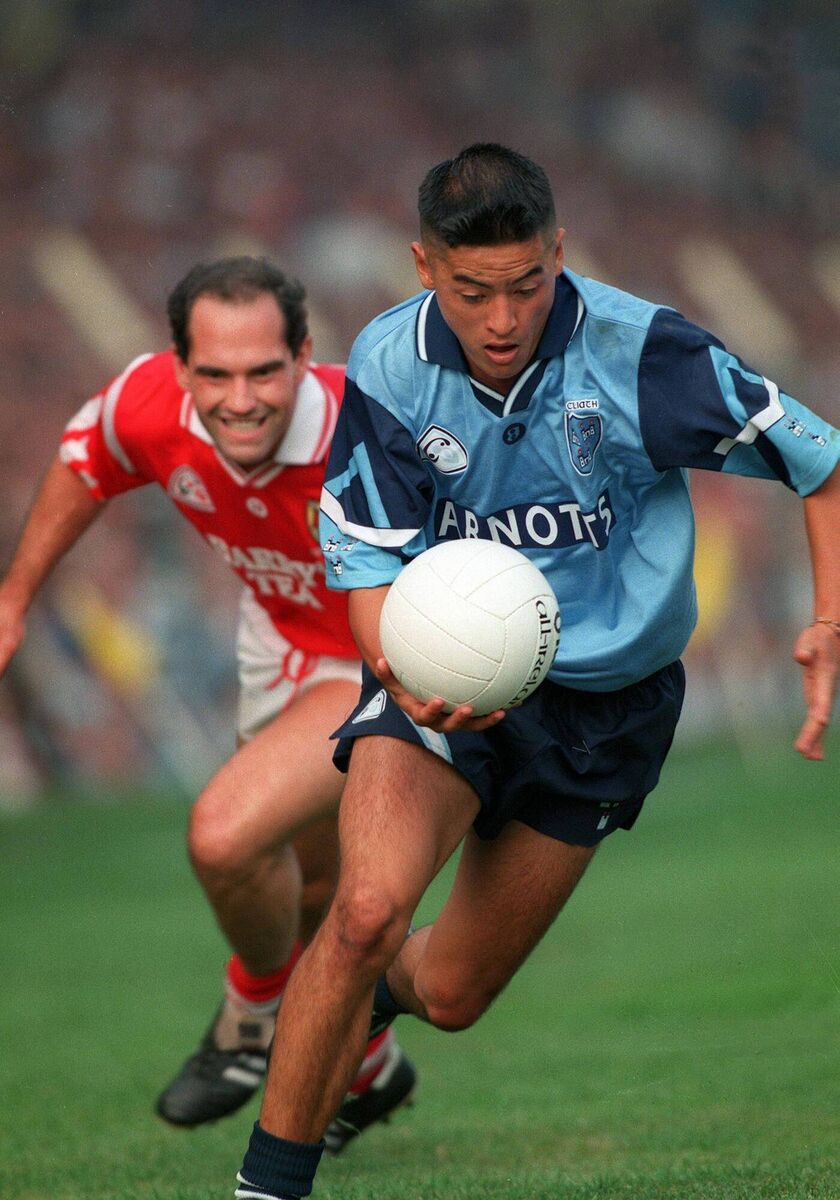

DECISIVE: Dublin's Jason Sherlock drills home the key goal past Cork keeper Kevin O'Dwyer in the 1995 All-Ireland SFC semi-final at Croke Park. They advanced to meet Tyrone on a 1-12 to 0-12 scoreline. Pic: David Maher/Sportsfile

THE noise.

When they think back on what was probably their day of days, what they remember most, even more than the colour and that magnificent clash of blue and red, is the noise.

“You had a headache going around in the parade, it was so loud,” Daniel Goulding would recall shortly after he retired. “The All Ireland final seemed quiet in comparison.”

“You could actually feel the vibration coming from the Hill walking past it in the parade,” Donncha O’Connor would similarly recount when he finished up with Cork.

That Dublin game was just one of eight All Ireland semi-finals Noel O’Leary played in. A month later he played in his third All-Ireland final. He was a veteran of 10 Kerry-Cork battles in Munster. Yet when the makers of Laochra Gael came to telling his story, he’d tell them, “Of all the games I ever played in, that [Dublin semi-final] was by far the best atmosphere I ever played in.”

Joe Kavanagh can understand why O’Leary though that. Back in the ’90s, Kavanagh played in a couple of All Irelands himself, electrifying the place each time with goals as good as any the old ground has seen. In 1995 he played in a Cork-Dublin All Ireland semi-final himself. Yet for all the big games he played in, or all the others he attended supporting his younger brother Derek, that 2010 semi-final stands out.

“It was the best atmosphere I’ve ever experienced up until the hurlers played and beat Limerick in the Páirc last May. That surpassed it and the semi-final a couple of months later was as good again. But until then that Dublin game was out on its own. The roof lifted that day.”

His brother Derek was partly responsible for that, kicking Cork’s last score of the day. It’d be his last for Cork. A month later, after winning that Celtic Cross he and his family had craved, he retired from inter-county football. And when he now looks back on it all, that Dublin game stands out. For the same reason everyone else seems to: The noise.

How big a factor was it? A week out from the game when Cork were playing their internal A-versus-B game, the stands in Páirc Uí Chaoimh were empty but its speakers, upon the recommendation of team sport psychologist Kevin Clancy, were blaring with recorded crowd noise.

“I remember thinking at the start, Feck it, this might be too much, this mightn’t work,” says Derek Kavanagh now. “But it did. Kevin’s point was that when you play Dublin in a packed Croke Park, you will not be able yourselves talk. It’d be completely different to even playing Kerry in an All Ireland final when a good bit of the crowd were neutrals.

“We’d to learn and rehearse that if you wanted to pass on something to a fella, you’d have to run over and grab his head and shout into his earlobes. Or rely on hand gestures and other forms of non-verbal communication. Leaving the Páirc that day, I felt prepared.”

Either side of that session Daniel Goulding and Donncha O’Connor were wearing ear pods, ‘Come On Ye Boys in Blue’ becoming the soundtrack of their fortnight as they practised frees and penalties that could be the difference between winning and losing.

Again, was it overkill? Or worth it if was worth a point?

Between them O’Connor and Goulding kicked 1-9 that day, 1-7 from dead balls. O’Connor alone kicked 1-3 in the last 15 minutes.

Like Kavanagh he felt steeled by his preparation. All informed by the idea that a Dublin-Cork knockout game in Croker had a different dynamic from almost any other game.

The noise.

Boom, boom, boom.

Wait, did we hear you say Jayo?

***

If ever there was a team who could identify with where the Cork footballers were in 2010, it’d be the Dublin side of 1995. They too had lost an All Ireland final three years earlier, lost a semi-final the year after that, then got back to the final only to lose again. In ’95 there was a desperation and obsession about them. Didn’t matter if they only fell over the line, they had to get over it.

Their only problem was in the semi-final they were encountering another group of Cork footballers that had a highly similarly profile. Billy Morgan’s side in 1993 had also lost a game to Derry that they felt they should have won, and then lost to Down as well in 1994.

“Cork were a bit like ourselves in terms of coming close without delivering,” John O’Leary observed in his autobiography. “They’d also got into the Dublin act of losing to the team that eventually won the All Ireland.”

For a measure of Dublin’s desperation and recognition of Cork’s threat, Paul Curran will point to something that happened within a couple of minutes of the throw in.

“Ciarán O’Sullivan was after a terrific Munster final, coming up from wing back and kicking two points from play. Jim Gavin was detailed to make sure that didn’t happen against us. And if you look back at the first touch O’Sullivan gets of the ball, Jim hauled him down straightaway. Today Jim and his FRC would have it down as a straight black card. But Jim’s mindset back then was, ‘I can’t let this fella up the field.” Everywhere else though Dublin were struggling to stem the red tide. Cork kicked five of the game’s opening seven scores.

“We were chasing shadows, out on our feet,” Jason Sherlock would write in his autobiography. “I was completely out of it. All I did was chase after Mark O’Connor’s heels.”

That was an individual battle that had attracted much intrigue leading into the game. Sherlock himself was just coming out of a minor team that had reached the previous year’s All Ireland semi-final and had brought a freshness to a veteran side. In the Leinster semi-final he kicked a decisive goal while his boot flew off, tormented Meath and kissed a ref on the cheek in the Leinster final. He played and approached the game like no one else. And at a time when Seán Óg Ó hAilpín was only a minor, he looked like no one else who played it either.

The night before the Cork game, Sherlock had attended Riverdance in the Point Theatre. “I left in awe of how those dancers and musicians were able to get such emotion out of people,” he’d write in Jayo. He started to picture it: what ways the next day he could similarly bring a crowd to its feet through his own dazzling footwork.

Mick Galvin would go on to have an exceptional game that day, finishing with four points from play in a low-scoring game, but probably his most important contribution was to vacate his position and leave Sherlock one-on-one on O’Connor.

“I squared him up, basketball-style,” Sherlock recalled. “Mark was powerful but not exceptionally mobile. So when I swivelled and turned, he slipped.” O’Connor would finish that year with an All Star as well as a county championship medal with Bantry, yet mention his name and that year and he’s often reduced to that slip, almost like Steven Gerrard with his in 2014.

As for Sherlock? His resultant goal changed everything. That game. That team. His life.

“All the belief that Cork had was sucked out of them,” he’d later reflect. “They went back into their shell. It was as if their game plan was in tatters.”

Shortly thereafter Podsie O’Mahony was withdrawn, much to Curran’s relief. Back then it was almost unheard of to use one of your three substitutions before halftime. Brian Stynes was running midfield yet Shay Fahy was introduced at wing forward. Brian Corcoran, meanwhile, who had been outstanding in the halfback line that season, was moved onto Galvin in the corner.

“I hated playing in the fullback line,” Corcoran wrote in his autobiography. “I was never a stopper.”

Even as Dublin took over control of the game, Curran wasn’t comfortable. “[Larry] Tompkins was on the 40. He was coming to the end but he was still able to contribute. You’d Kavanagh, Colin Corkery. Serious ballplayers.”

With a minute to go though Dublin were four up. Curran ended up in the same vicinity of the field as Steven O’Brien, Cork’s centre back. Back in 1990 they’d been two of the youngest members of the Irish International Rules squad that had gone down under, sharing many a pint together. The bond was still intact enough for O’Brien now to share a quip. “Will you take the draw?” Curran smiled back. Although O’Brien had a capacity for late goals, as he’d shown the previous year against Kerry, Dublin weren’t going to be denied. After Larry Tompkins kicked his last-ever point in Croke Park, Pat McEnaney blew it up. Dublin had won by a goal. Sherlock’s goal.

As he exchanged jerseys with O’Connor and was escorted by security off the field, the Hill reverberated to its own take to a popular track by the Outhere Brothers.

Boom, boom, boom. Let me hear you say Jayo – Jayo!

***

Fifteen years later, the Hill and the GAA had another darling. Though for the first time since 1994 Dublin no longer featured Jason Sherlock in their lineup, his absence had been more than filled by the emergence of one Bernard Brogan.

“He was the ultimate striker around then,” says Paul Flynn. “He could make a shot out of anything. He’d the power and pace to get away from his man and then had this ability to drop the ball and strike it so quickly and accurately. You could never block one of his shots. He was untouchable. Unmarkable.”

Like Sherlock 15 years earlier Brogan had come into the semi-final as the talk of the town. Only a fortnight earlier he’d shot nine points, four from play, and no wides to strip Tyrone off their All Ireland belt.

Against Cork though he would go and take it to another level. Two minutes in and the noise around the ground that had stunned O’Connor and Goulding in the warmup was exceeded as Brogan struck past Alan Quirke down by the same Canal End Sherlock shot past Kevin O’Dwyer 15 years earlier.

“I remember Pat Spillane was critical of how Ray Carey defended it but Ray actually defended it as I would have myself,” says Eoin Cadogan. “When you’re marking a player like Brogan, you can’t afford to allow him out in front. Because he had a real quick turn and could kick off either foot. It’s just that they happened to play a brilliant ball in over the top.

“But the important thing was it didn’t faze us. Watching the game back there recently, what struck me was how strong our body language was. How calm it was. We fully believed in each other and what we were about.”

That had been learned and earned the hard way. Derek Kavanagh by then had played in a couple of All Ireland finals, just like his older brother, but unlike Joe he hadn’t the consolation to say that he had at least expressed himself in them.

“I remember being in Croke Park an hour or two after the 2007 final and looking out on the pitch and it hit me: it was just another pitch. It had been just another game. All the razzmatazz, all the hype, all the media, all the crowd: gone. They no longer gave a hoot about it. You’d made too big a deal about it. Why had you allowed yourself get sucked into all the hype? All you wanted to do was rewind back three hours and have a chance to do it all over again.

“As a young fella I’d been obsessed about it," Kavanagh says. "I can’t remember a lot of the games I played in myself but I can name you every Cork team that played in Croke Park in the ‘80s and ’90s. I was standing right behind the goal in the Canal End when Jayo scored into it against Cork. But when I became a player that passion often led to paralysis by analysis.”

Towards the end of his career he leant a lot into sport psychology. Read up on it. Collaborated with Clancy. Together they drew up some affirmations that he could lean on when the nerves were jangling, when the belief was maybe wavering. “To maybe trick myself. Empower myself. Whatever way you look at it.”

He’d look at them in the dressing room before the game, repeat themselves in the heat of battle if necessary. I’m good enough. We’re good enough. We still have this. We’re doing this.

By then it wasn’t just Kavanagh who knew himself. So did Counihan. They could all read each other. “As much as I got better at the mental game, I’d say Conor had figured me out and made the calculation: it’s better for us and you if you come on at the end. And he was right. That’s just being totally honest about it. I wasn’t like some of the other lads like Goulding who was an All Star talent with no nerves or doubts. It was easier for me to come off the bench. And because I knew it was my last year, I brought that element of a mad-man feck-it mindset to it as well.”

Even with 15 minutes to go as he warmed up along the touchline, he had some doubts. “But then we won the penalty. And when I saw Donncha standing over it, I thought, we have a great chance here of still doing this. Next thing he stuck it and shortly after that I was on. To be honest, it was a privilege to be thrown in then. All that momentum, all that experience, we had.”

That was the difference in the end. By then Paul Flynn was on the field but this was the year before he’d win the first of four straight All Stars. This altitude was new to him and most of his teammates.

“You have to get yourself into that position to really appreciate and figure out how the oxygen is thinner there before you can operate up there consistently,” says Flynn now. “You build up that experience layer by layer. Cork at that point had it. And we hadn’t. We froze. All the clichéd stuff – playing the moment, staying present rather than waiting for the final whistle – we hadn’t yet learned.”

“That day there was a break in play and I looked up at the screen,” Philly McMahon recall in his book The Choice. “Four minutes left and we were two points up. We could be in the final in a few minutes, I thought to myself. That was my biggest mistake. I had switched off from the process to the outcome.

“Before I knew it, the game had slipped away from us. These big monsters started running directly at us and we panicked. I know I panicked a bit. Going for a ball, Colm O’Neill got out in front of me, and instead of going with him, I tried to catch a hold of him. That was their equaliser.

“From that day on, I swore I’d never think about how long was left in a game again. Now I have a thing in my head where I want the referee to play an extra 10 minutes all the time. I don’t want games to end. I want them to last. I want to embrace them. But the stakes were different that day against Cork and it was the first time I’d ever been in a position like that.”

Cork in contrast kept with their process. “Even when Brogan put the ball over the bar to make it a one-point game again,” recalls Cadogan, “Alan Quirke gave the emergency-kick signal for an overload. No panic. But as it happened, the ref blew it up then.”

A month later they would do what the Dublin team of ’95 did: stumble over the line by beating an Ulster team (Down) by a point in the final. It was the least they deserved. Sometimes Cadogan hears people complain that they only won one in a row and it “pisses me off”. He’d go on to play in an All Ireland hurling final and win Munster titles with legends like Patrick Horgan and yet he’ll always say, “That group of 2010 were the finest bunch I’ve ever been involved with.”

Paul Flynn will vouch how exceptional they were. Later on that decade Dublin would form some remarkable rivalries with Kerry, Mayo and Donegal but he’ll point out their first nemesis and obstacle was Cork. The “monsters” that McMahon referenced – O’Neill, Kissane, Alan O’Connor, the lot of them – was an apt phrase.

“In terms of conditioning, they were phenomenal, the market leaders,” says Flynn now. “And they had lots of football too. I sometimes remind [Sunday Game and former GPA executive colleague] Donal Óg [Cusack] that Cork won an All Ireland since 2005. That was an exceptional generation of Cork footballers.” Flynn is just back from holiday in Spain with the star of 2010 and his family: Bernard Brogan finished that game against Cork with 1-7, all but one point from play, and the season itself as Footballer of the Year. He hasn’t been around so long enough to get a gauge of the mood about Saturday's prelininary All-Ireland quarter-final against Cork but he’s a bit apprehensive about it.

“This Cork team are not dissimilar to the team of 2010. In [Ian] Maguire and Colm O’Callaghan they’ve really good big men around the middle. They run the ball well. They’ve an inside line that can hurt teams. They’re a dangerous opponent. Something about Kerry and Dublin bring out something in them: this sense, ‘We’re Cork.’”

And as we know, every 15 years Dublin-Cork tends to produce something special.